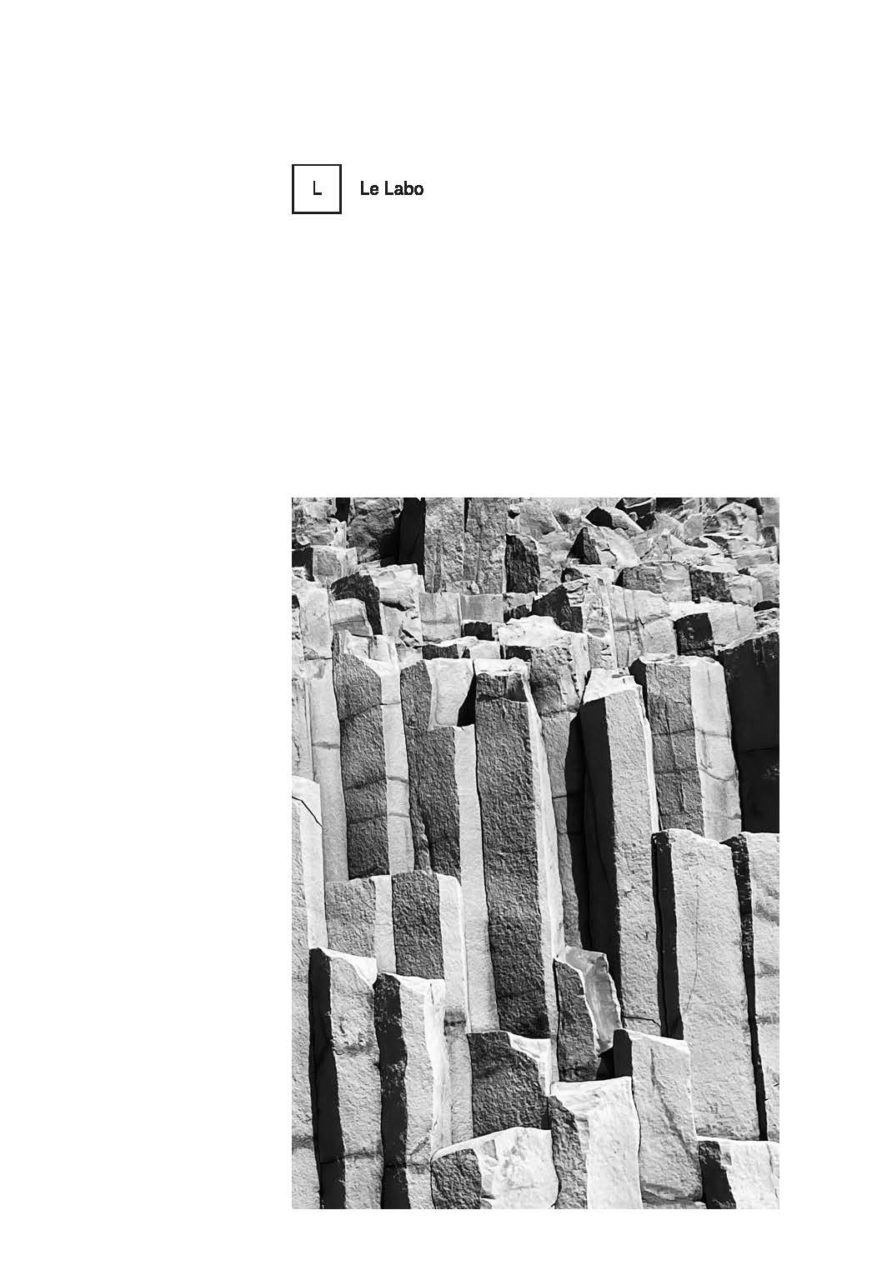

Beauty came to us in stone

10 01 25 — 19 01 25

Peter Stoffel

Vernissage jeudi 9 janvier 2025, 18h

Lecture et dédicace du livre de Peter Stoffel ISLAND (Beauty came to us in stone), édition fink, Zürich, 2024

20h – intervention sonore « sound stone intermezzi » par Thomas Schunke.

L’exposition est visible jusqu’au 19 janvier.

Le Labo est ouvert mercredi et vendredi de 16h à 19h et samedi de 14h à 17h et sur rendez-vous: contact@espacelabo.net

Beauty came to Us in Stone

09 01 25 — 19 01 25

Peter Stoffel

Beauty Came to Us in Stone

«So we meet again in Arolla,» Stoffel grins, prodding the Schublig sausages that arc

and twist over glowing embers at 2,000 meters above sea level. Years after writing

about our first meeting here for his exhibition catalogue at Kunstmuseum Solothurn,

we stand again at Europe’s highest campground. This time Stoffel has just returned

from Iceland, and the northern wilderness has left its mark on his artistic vision. The

sausages, still made by his own hands, remind me of my previous vegan protestations,

now worn smooth by time like river stones. He describes how the northern lights

had danced above active volcanoes – nature’s own version of his paintings, where

fluid energies course through solid forms. «Like that,» he says, gesturing at the

sausages curling in the heat, «everything is always in motion, even stone.»

I’m watching him from a precarious camp stool, feeling distinctly out of

place – still a city dweller who prefers his nature framed by hotel windows.

Around us, the highest campground in Europe stretches like a shelf cut

into eternity. Beyond, the Alps rear up with a static majesty that seems

tame compared to the liquid fire Stoffel witnessed in Iceland.

As darkness seeps up from the valleys, Stoffel begins to talk. His voice mingles

with the hiss of fat dripping onto coals. «In Reykjavik,» he says, turning

the meat with careful attention, «I watched the aurora paint the sky while

below, magma pushed against the earth’s crust. Light above, fire below – and

between them, the landscape constantly transforming.» Somewhere in the

darkness floats the familiar chime of unseen cattle bells, interwoven with the

wind’s sighing through the high passes. The Alps may appear immutable and

fixed, but Stoffel sees them through eyes recently calibrated to Iceland’s raw

geology, where creation and destruction perform their eternal dance.

«Look there,» he says suddenly, pointing with his fork toward where the

Pigne d’Arolla catches the day’s last light. The mountain appears to ripple, its

solidity momentarily questionable. «That’s what I’m after. Not the mountain

as object, but as event. A slow explosion caught in mid-burst.»

The meat is done. We eat in the gathering dark, watched by peaks that have become

massive absences against the star-bright sky. Last time, Stoffel spoke of painting

as an array of byzantine connections. Now, tempered by northern ice and fire, his

words carry new weight. «When you’ve seen the ground crack open and witnessed

light paint itself across the entire sky, you realize everything is fluid. Even these Alps

are just temporary formations, frozen moments in an endless flow.» «Like love,» he

says, grinning. «Either close enough to swallow or so vast you can’t see its edges.»

Night proper arrives with alpine suddenness. The fire dies to embers that

mirror the stars, and Stoffel’s voice takes on a different timbre. He speaks

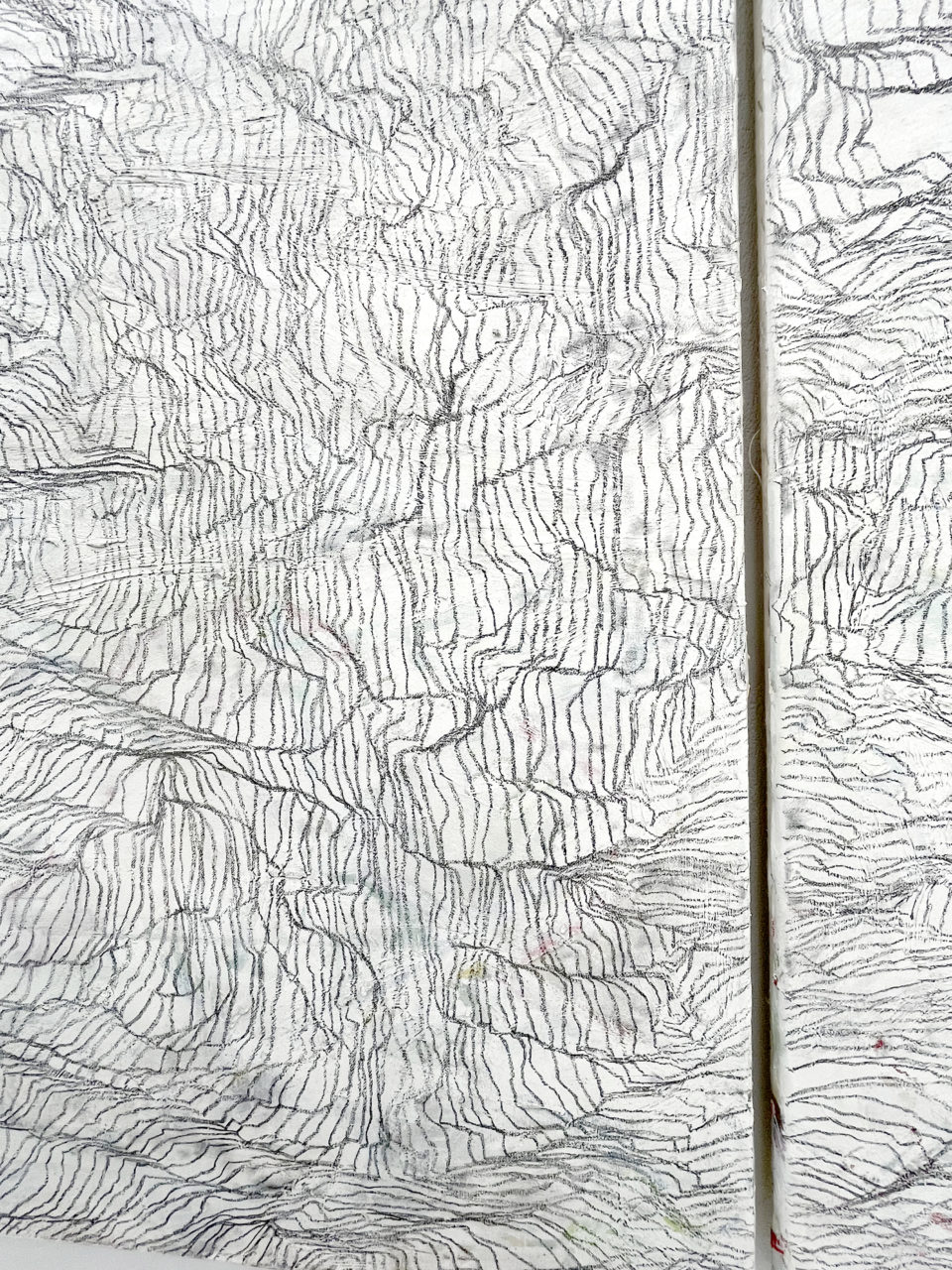

of painting as cartography of the impossible – mapping territories that

exist between states of being. «Like the moment when magma becomes

stone, or when the aurora’s ethereal light seems to solidify into momentary

architecture.» His hands move in the darkness, sketching invisible forms.«I still want to paint an atlas,» he says, echoing his words from years ago,

«layer all images into one thick book and move through it like a worm.

Vertical, horizontal, diagonal.» He pauses. «To digest it, you understand?

To process it through the body. But now I understand better what that

means. Not just layers of images, but layers of time itself – glacial, tectonic,

cosmic. A book where every page is alive with transformation.»

The cold is becoming insistent. High above, unseen glaciers shift and groan – a

sound like the earth remembering. Stoffel feeds the fire and continues. He describes

paintings that operate like geological processes – compression, erosion, folding.

Canvases where space itself appears to bend and time becomes visible as texture.

Up here, his words acquire a peculiar resonance. The darkness around us

vibrates with possibility – not empty space but raw potential, like the instant

before water freezes into ice, when molecules pause to contemplate their future

architecture. The night air seems charged with this same suspended energy, as

if we’re floating in that ancient space where elements first learned to dance.

Morning arrives like a slow tide of light. The peaks materialize from darkness,

solid again but somehow altered by our night’s conversation. They read now like

enormous paintings in progress, their surfaces alive with incident and possibility.

Stoffel is already up, naturally, busy with breakfast and still talking. He wants

to see mountains from below. He wants to paint air currents and deep time.

He wants to fold space back on itself until it reveals its hidden symmetries.

I pack my gear, watching him gesture at the awakening landscape. Here at altitude,

surrounded by stone and sky, his obsessions make a different kind of sense. His

paintings aren’t representations of mountains – they’re investigations into how the

world assembles and disassembles itself, moment by moment, particle by particle.

The peaks loom above us, patient as paint drying, permanent as a gesture caught

in mid-stroke. Stoffel is still talking as I leave, his words merging with the morning

wind, becoming part of the mountain’s endless conversation with itself.

Tirdad Zolghadr

Vous devez être connecté pour poster un commentaire.